|

This section contains the following topics: |

It is extremely important in data modeling, and in systems development in general, to choose clear and well thought out names for objects. The result of your efforts will be a clear, concise, and unambiguous model of a business area.

Naming standards and conventions are identical for all types of logical models, including both the Entity Relationship diagrams (ERD) and Key-based (KB) diagrams.

The most important rule to remember when naming entities is that entity names are always singular. This facilitates reading the model with declarative statements such as "A FLIGHT <transports> zero or more PASSENGERs" and "A PASSENGER <is transported by> one FLIGHT." When you name an entity, you are also naming each instance. For example, each instance of the PASSENGER entity is an individual passenger, not a set of passengers.

Attribute names are also singular. For example, "person-name," "employee-SSN," "employee-bonus-amount" are correctly named attributes. Naming attributes in the singular helps to avoid normalization errors, such as representing more than one fact with a single attribute. The attributes "employee-child-names" or "start-or-end-dates" are plural, and highlight errors in the attribute design.

A good rule to use when naming attributes is to use the entity name as a prefix. The rule here is:

Using this rule, you can easily validate the design and eliminate many common design problems. For example, in the CUSTOMER entity, you can name the attributes "customer-name," "customer-number," "customer-address," and so on. If you are tempted to name an attribute "customer-invoice-number," you use the rule to check that the suffix "invoice-number" tells you more about the prefix "customer." Since it does not, you must move the attribute to a more appropriate location, such as INVOICE.

You may sometimes find that it is difficult to give an entity or attribute a name without first giving it a definition. As a general principle, providing a good definition for an entity or attribute is as important as providing a good name. The ability to find meaningful names comes with experience and a fundamental understanding of what the model represents.

Since the data model is a description of a business, it is best to choose meaningful business names wherever that is possible. If there is no business name for an entity, you must give the entity a name that fits its purpose in the model.

Not everyone speaks the same language. Not everyone is always precise in the use of names. Since entities and attributes are identified by their names in a data model, you need to ensure that synonyms are resolved to ensure that they do not represent redundant data. Then you need to precisely define them so that each person who reads the model can understand which facts are captured in which entity.

It is also important to choose a name that clearly communicates a sense of what the entity or attribute represents. For example, you get a clear sense that there is some difference among things called PERSON, CUSTOMER, and EMPLOYEE. Although they can all represent an individual, they have distinct characteristics or qualities. However, it is the role of the business user to tell you whether or not PERSON and EMPLOYEE are two different things or just synonyms for the same thing.

Choose names carefully, and be wary of calling two different things by the same name. For example, if you are dealing with a business area which insists on calling its customers "consumers," do not force or insist on the customer name. You may have discovered an alias, another name for the same thing, or you may have a new "thing" that is distinct from, although similar to, another "thing." In this case, perhaps CONSUMER is a category of CUSTOMER that can participate in relationships that are not available for other categories of CUSTOMER.

You can enforce unique naming in the modeling environment. This way you can avoid the accidental use of homonyms (words that are written the same but have different meanings), ambiguous names, or duplication of entities or attributes in the model.

Defining the entities in your logical model is essential to the clarity of the model and is a good way to elaborate on the purpose of the entity and clarify which facts you want to include in the entity. Undefined entities or attributes can be misinterpreted in later modeling efforts, and possibly deleted or unified based on the misinterpretation.

Writing a good definition is more difficult than it may seem at first. Everyone knows what a CUSTOMER is, right? Just try writing a definition of a CUSTOMER that holds up to scrutiny. The best definitions are created using the points of view of many different business users and functional groups within the organization. Definitions that can pass the scrutiny of many, disparate users provide a number of benefits including:

Most organizations and individuals develop their own conventions or standards for definitions. In practice you will find that long definitions tend to take on a structure that helps the reader to understand the "thing" that is being defined. Some of these definitions can go on for several pages (CUSTOMER, for example). As a starting point, you may want to adopt the following items as a basic standard for the structure of a definition, since IDEF1X and IE do not provide standards for definitions:

A description should be a clear and concise statement that tells whether an object is or is not the thing you are trying to define. Often such descriptions can be fairly short. Be careful, however, that the description is not too general or uses terms that are not defined. Here are a couple of examples, one of good quality and one that is questionable:

Example of good description:

A COMMODITY is something that has a value that can be determined in an exchange.

This is a good description since, after reading it, you know that something is a COMMODITY if someone is, or would be, willing to trade something for it. If someone is willing to give you three peanuts and a stick of gum for a marble, then you know that a marble is a COMMODITY.

Example of bad description:

A CUSTOMER is someone who buys something from our company.

This is not a good description since you can easily misunderstand the word "someone" if you know that the company also sells products to other businesses. Also, the business may want to track potential CUSTOMERs, not just those who have already bought something from the company. You can also define "something" more fully to describe whether the sale is of products, services, or some combination of the two.

It is a good idea to provide typical business examples of the thing being defined, since good examples can go a long way to help the reader understand a definition. Comments about peanuts, marbles or something related to your business can help a reader to understand the concept of a COMMODITY. The definition states that a commodity has value. The example can help to show that value is not always measured in money.

You can also include general comments about who is responsible for the definition and who is the source, what state it is in, and when it was last changed as a part of the definition. For some entities, you may also need to explain how it and a related entity or entity name differ. For instance, a CUSTOMER might be distinguished from a PROSPECT.

An individual definition can look good, but when viewed together they can be circular. Without some care, this can happen with entity and attribute definitions.

Example:

It is important when you define entities and attributes in your data model that you avoid these circular references.

It is often convenient to make use of common business terms when defining an entity or attribute. For example, "A CURRENCY-SWAP is a complex agreement between two PARTYs where they agree to exchange cash flows in two different CURRENCYs over a period of time. Exchanges can be fixed over the term of the swap, or may float. Swaps are often used to hedge currency and interest rate risks."

In this example, defined terms within a definition are highlighted. Using a style like this makes it unnecessary to define terms each time they are used, since people can look them up whenever needed.

If it is convenient to use, for example, common business terms that are not the names of entities or attributes, it is a good idea to provide base definitions of these terms and refer to these definitions. A glossary of commonly used terms, separate from the model, can be used. Such common business terms are highlighted with bold-italics, as shown in the previous example.

It may seem that a strategy like this can at first lead to a lot of going back and forth among definitions. The alternative, however, is to completely define each term every time it is used. When these internal definitions appear in many places, they need to be maintained in many places, and the probability that a change will be applied to all of them at the same time is very small.

Developing a glossary of common business terms can serve several purposes. It can become the base for use in modeling definitions, and it can, all by itself, be of significant value to the business in helping people to communicate.

As with entities, it is important to define all attributes clearly. The same rules apply. By comparing an attribute to a definition, you should be able to tell if it fits. However, you should be aware of incomplete definitions.

Example:

account-open-date

The date on which the ACCOUNT was opened. A further definition of what "opened" means is needed before the definition is clear and complete.

Attribute definitions generally should have the same basic structure as entity definitions, including a description, examples, and comments. The definitions should also contain, whenever possible, validation rules that specify which facts are accepted as valid values for that attribute.

A validation rule identifies a set of values that an attribute is allowed to take; it constrains or restricts the domain of values that are acceptable. These values have meanings in both an abstract and a business sense. For example, "person-name," if it is defined as the preferred form of address chosen by the PERSON, is constrained to the set of all character strings. You can define any validation rules or valid values for an attribute as a part of the attribute definition. You can assign these validation rules to an attribute using a domain. Supported domains include text, number, datetime, and blob.

Definitions of attributes, such as codes, identifiers, or amounts, often do not lend themselves to good business examples. So, including a description of the attribute's validation rules or valid values is usually a good idea. When defining a validation rule, it is good practice to go beyond listing the values that an attribute can take. Suppose you define the attribute "customer-status" as follows:

Customer-status: A code that describes the relationship between the CUSTOMER and our business. Valid values: A, P, F, N.

The validation rule specification is not too helpful since it does not define what the codes mean. You can better describe the validation rule using a table or list of values, such as the following table:

|

Valid Value |

Meaning |

|---|---|

|

A: Active |

The CUSTOMER is currently involved in a purchasing relationship with our company. |

|

P: Prospect |

Someone with whom we are interested in cultivating a relationship, but with whom we have no current purchasing relationship. |

|

F: Former |

The CUSTOMER relationship has lapsed. In other words, there has been no sale in the past 24 months. |

|

N: No business accepted |

The company has decided that no business will be done with this CUSTOMER. |

When a foreign key is contributed to a child entity through a relationship, you may need to write a new or enhanced definition for the foreign key attributes that explains their usage in the child entity and can assign a rolename to the definition. This is certainly the case when the same attribute is contributed to the same entity more than once. These duplicated attributes may appear to be identical, but because they serve two different purposes, they cannot have the same definition.

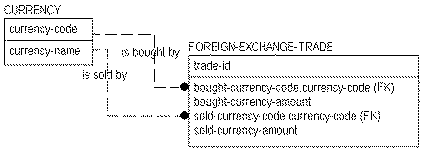

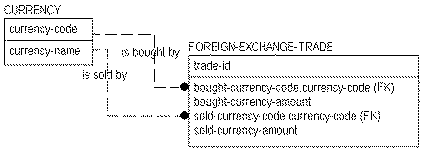

Consider the following example shown in the figure below. Here you see a FOREIGN-EXCHANGE-TRADE with two relationships to CURRENCY.

The key of CURRENCY is "currency-code," (the identifier of a valid CURRENCY that you are interested in tracking). You can see from the relationships that one CURRENCY is "bought by," and one is "sold by" a FOREIGN-EXCHANGE-TRADE.

You also see that the identifier of the CURRENCY (the "currency-code") is used to identify each of the two CURRENCYs. The identifier of the one that is bought is called "bought-currency-code" and the identifier of the one that is sold is called "sold-currency-code." These rolenames show that these attributes are not the same thing as "currency-code."

It would be somewhat silly to trade a CURRENCY for the same CURRENCY at the same time and exchange rate. So for a given transaction (instance of FOREIGN-EXCHANGE-TRADE) "bought-currency-code" and "sold-currency-code" must be different. By giving different definitions to the two rolenames, you can capture the difference between the two currency codes.

|

Attribute/Rolename |

Attribute Definition |

|

currency-code |

The unique identifier of a CURRENCY. |

|

bought-currency-code |

The identifier ("currency-code") of the CURRENCY bought by (purchased by) the FOREIGN-EXCHANGE-TRADE. |

|

sold-currency-code |

The identifier ("currency-code") of the CURRENCY sold by the FOREIGN-EXCHANGE-TRADE. |

The definitions and validations of the bought and sold codes are based on "currency-code." "Currency-code" is called a base attribute.

The IDEF1X standard dictates that if two attributes with the same name migrate from the same base attribute to an entity, then the attributes must be unified. The result of unification is a single attribute migrated through two relationships. Because of the IDEF1X standard, foreign key attributes are automatically unified as well. If you do not want to unify migrated attributes, you can rolename the attributes at the same time that you name the relationship, in the Relationship Editor.

Business rules are an integral part of the data model. These rules take the form of relationships, rolenames, candidate keys, defaults, and other modeling structures, including generalization categories, referential integrity, and cardinality. Business rules are also captured in entity and attribute definitions and validation rules.

For example, a CURRENCY entity defined either as the set of all valid currencies recognized anywhere in the world, or could be defined as the subset of these which our company has decided to use in its day to day business operations. This is a subtle, but important distinction. In the latter case, there is a business rule, or policy statement, involved.

This rule manifests itself in the validation rules for "currency-code." It restricts the valid values for "currency-code" to those that are used by the business. Maintenance of the business rule becomes a task of maintaining the table of valid values for CURRENCY. To permit or prohibit trading of CURRENCYs, you simply create or delete instances in the table of valid values.

The attributes "bought-currency-code" and "sold-currency-code" are similarly restricted. Both are further restricted by a validation rule that says "bought-currency-code" and "sold-currency-code" cannot be equal. Therefore, each is dependent on the value of the other in its actual use. Validation rules can be addressed in the definitions of attributes, and can also be defined explicitly using validation rules, default values, and valid value lists.

| Copyright © 2009 CA. All rights reserved. | Email CA about this topic |