Virtual appliances are the key concept in the application model.

A virtual appliance is an instantiable object that consists of a boundary and an interior. The boundary includes everything necessary to configure the appliance, bind it to data on external storage volumes and connect it to other appliances. The interior consists of a virtual machine and a boot volume that contains the OS, configuration files and application software that runs inside the appliance.

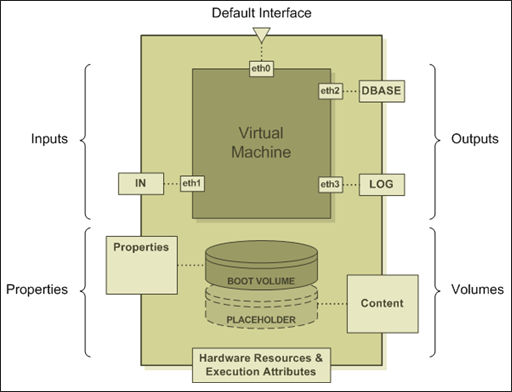

The figure above shows in more detail the anatomy of a typical virtual appliance. The boundary of the appliance consists of the following elements:

The interior of the appliance consists of a virtual machine and a boot volume. The boot volume is configured with a suitable version of Linux, and all other software packages and scripts that are needed for the appliance to work. The virtual machine is configured to boot from the boot volume and has several virtual network interface cards.

The eth0 vNIC is always set up as a default interface, which gives you the ability to log onto the appliance, install software and troubleshoot it, the same way you would do with any remote server.

In addition, CA AppLogic creates a separate vNIC for each terminal (input or output) defined on the boundary of the appliance. While it is possible to direct all traffic in and out of the appliance through a single vNIC, having a separate vNIC per terminal makes it easy for CA AppLogic to shape and monitor network traffic, enforce connection protocols and improve security.

The boundary contains a set of appliance-specific properties, or parameters which you can use to configure the appliance. When you start the appliance, CA AppLogic automatically creates an environment variable for each property and initializes it with the value that you have assigned to that property. In addition, CA AppLogic propagates the property values into one or more of the configuration files contained on the boot volume. This makes it easy to use properties as the primary mechanism for configuring appliances.

The boundary may also contain one or more volume placeholders. A placeholder is a predefined slot for a storage volume. You fill up the slot by configuring the appliance with the name of a volume to mount. This gives you the virtual equivalent of a removable disk. Many of the appliances use this mechanism to access content, such as HTML pages, custom code, or databases.

CA AppLogic also assigns to each appliance a hardware resource budget that includes a set of three ranges that define minimum and maximum CPU use, memory use, and bandwidth use for the appliance.

Finally, CA AppLogic associates with each appliance a set of execution attributes that affect the way the system schedules and runs the appliance. You are likely to use frequently two of those attributes - the start order value, and the migratable flag. The start order allows you to specify and change the order in which appliances from the same application start, accounting for any dependencies among them. The migratable flag is true by default and indicates to CA AppLogic that it is OK to migrate this appliance from one server to another at the scheduler's discretion. Setting this flag to false will allow you to keep the appliance on a specific server.

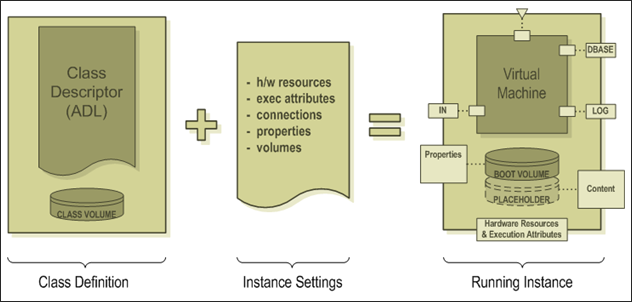

CA AppLogic treats virtual appliances as first-class component objects. When you create a new type of appliance, you are really creating is a class of appliances, letting CA AppLogic know how to manufacture such appliances (named instances of the class) on demand. Because appliance classes are templates for making instances, they cannot be executed. An actual running application contains only instances, configured and interconnected to work together.

The figure above shows how CA AppLogic instantiates classes. Every class has an associated class descriptor, which defines:

The complete definition of a class consists of its class descriptor and the full set of class volumes identified in the descriptor, including their content - the OS, application software and scripts which together define the behavior of the appliance.

Ordinary appliance classes can produce any number of instances. Singletons are classes that are limited to a single instance at a time. Singletons are useful when you need to edit or troubleshoot a class. Because only instances can run on the system, you always need an instance to test and troubleshoot the class. Singletons make this process simpler. They allow you to test and troubleshoot the instance, and then generate a new class automatically from the working instance.

The class definition is not sufficient to create a usable running instance. To do this, CA AppLogic also needs to know the instance settings - a set of parameters that define how the instance is to be connected, configured and executed. The instance settings consist of specific values for hardware resources, execution attributes, terminal connections, appliance properties and names of external volumes.

To create an instance, CA AppLogic interprets the class descriptor and creates a virtual machine with one virtual network adapter for each terminal and a virtual block device for each volume. It then creates an instance of a virtual network interface for each of the adapters and binds it to the appropriate adapter.

Next, the system creates a virtual volume instance for each volume specified in the descriptor by replicating the appropriate class volume and binds it to the corresponding block device.

The newly created instance is configured using the property values, usually by modifying the configuration files identified in the class definition and located on one or more of the instantiated volumes. Because each instance volume is a copy of the respective class volume, these modifications are private to the instance.

CA AppLogic then starts the VM which results in booting and starting the various services configured in the appliance. It uses the hardware resources and execution attributes to control the starting, placement, scheduling and migration of the newly minted instance.

CA AppLogic separates the configuration and connection data which is specific for each appliance instance from the information common to all appliances of a given class, including OS code, application engine code, and the configuration parameters needed to make them work together.

Unlike execution attributes which can be applied to any appliance, you can define configuration parameters specific for each appliance class. CA AppLogic provides a property mechanism for defining and editing a set of such configuration parameters through a universal property interface.

To take advantage of the property mechanism, you define the properties by specifying their names, data types and default values as part of the class definition. You can also select one or more of the configuration files located on the volumes of the appliance as targets for the property values.

Inside an appliance instance, you can access a property value in one of two ways:

For each property on the boundary of the appliance, CA AppLogic defines an environment variable named after the property. At boot time, the value of the variable is initialized to the value assigned to the property. This makes properties easily accessible to daemons, utilities and scripts that execute within the appliance.

Note: A property defined on an appliance can be used to set values of one or more parameters located in text-based configuration files. To map a property of the appliance to a parameter in a configuration file, you need to tag the value in the file with a special tagged comment, identifying the name of the property you are trying to map. When the property is set, CA AppLogic will replace the value found in the file with the value assigned to the property.

CA AppLogic terminals are connection points for logical interactions between appliances. The terminal abstraction is designed so that existing software packages inside virtual appliances can communicate through terminals without requiring modification.

A terminal can be an input or an output. Inputs are terminals for accepting network connections. Outputs are terminals for originating network connections. With respect to the flows of requests and data, both types of terminals are bi-directional. A terminal consists of a network name, a virtual network adapter and a virtual network interface.

When an output of one appliance is connected to an input of another appliance, CA AppLogic creates a virtual wire between their respective virtual network interfaces and assigns virtual IP addresses to both ends of the connection.

Note: Virtual IP addresses are only there for the sake of the software running inside the VM. They are not actual, routable network addresses. The actual traffic on the connection is delivered through the virtual wire.

To the software running in a virtual appliance, terminals appear as named network hosts. An input defines a host name on which a server such as Apache can listen for incoming connection requests. When left unconnected, an output is visible inside the virtual machine as an "unreachable host". When connected to an input of another appliance, the same output acts as a valid network host, to which connections are established. If you logon to the appliance and ping a connected output, you will see that the name of the output resolves to the IP address of the input of the other appliance to which the output is connected.

Note: Terminals eliminate references to other appliances and servers.

The code running inside an appliance will see a "network" that consists only of few hosts, one for each terminal defined on the boundary of the appliance. This makes it possible to connect different instances of the same appliance in different structures without modifying the configuration of the appliance.

For example, if you are building an appliance that needs access to a database server, you may define an output for accessing that database and call it DBASE. When configuring the JDBC driver inside your appliance, you simply set the name of the output "DBASE" as the host name of the target database server. At runtime, each instance of your appliance may be connected to a different database server without you having to change the target host name for the JDBC driver - the same host name "DBASE" will automatically resolve to the correct IP address of the database server, to which the particular instance is connected.

For each terminal you can specify what protocol(s) are allowed on it. This has the effect of creating a virtual firewall on the terminal, letting in or out only the allowed protocols. As an added bonus, when you are setting up the application, CA AppLogic helps ensure that only terminals with matching protocols are connected to each other. So, if the software inside your appliance is configured to work with MySQL through the DBASE output, you can declare DBASE's protocol as MYSQL to prevent someone from accidentally connecting it to an Oracle server.

Note: You can declare any terminal as mandatory, letting CA AppLogic know that your appliance cannot work without being connected to this kind of external service. CA AppLogic will refuse to start an application, if a mandatory terminal is left unconnected, and it will let you know which terminal you have forgotten to connect.

Each appliance needs at least one storage volume - the one from which it boots. These volumes are provided as part of the class definition of the appliance and instantiated whenever an instance of the appliance is created. It is often useful to define your appliances with placeholders for additional volumes. When you define a placeholder, it becomes a "slot", into which you can later plug in an external volume.

The volumes you can "plug" into a placeholder slot are known as application volumes. You create an application volume explicitly, by executing the appropriate command and specifying a name, storage size and the type of the desired file system. You can mount application volumes on the CA AppLogic controller to transfer data in and out of them.

For example, it is useful to define a web server appliance with two volumes - a boot volume and a content volume. The boot volume contains the software and configuration files needed to boot Linux and run an Apache web server. This volume becomes part of the class definition and is instantiated for each instance of the appliance.

The content volume, however, is a placeholder for an application volume that will contain the HTML files, static images and scripts for a specific website. Configuring an instance of the web server appliance with a reference to the content volume produces an instance of an Apache web server that will serve the particular website. The pages and other content for this web server will be placed on the content volume.

Tip: You can use a single application volume to deploy content for multiple web servers. A simple way to do this is to add a property that specifies the base directory on the volume, from which the given appliance would access the content. This makes it easy to configure several web servers with the same content volume, while setting up each instance to serve content from a different directory.

The same pattern can be used to design a generic J2EE server configured with a volume (and base path on it) that contains the EJB packages for a particular application function, or a generic database server configured with a volume and path containing a specific database.

In fact, using this combination of application volume plus a directory path property makes it possible to combine the user interface, static content, code and data of the application on a single volume, making it easier to deploy, modify and maintain.

|

Copyright © 2013 CA Technologies.

All rights reserved.

|

|