* # and ‘@’ are not allowed in label names.

Several psychological factors are also relevant. Human short-term memory has difficulty retaining more than seven (plus or minus two) "chunks" of information. This is significant if unfamiliar names have to be remembered for short periods of time; for instance, when noting down the name of a program that has crashed, or when looking up a code value for an input display.

Remembering an arbitrary code such as ‘X1274ZF’ is more difficult than remembering a meaningful one of equivalent length which can be "chunked" into a lower number of known components. For example, although ‘UDSPCUS’ is also seven letters long, to someone familiar with OS/400 naming conventions it can be remembered as only three elements (U + DSP + CUS).

Where a name is made up of subcodes, the number of possible ambiguous interpretations is greatly reduced if the subcodes always have the same starting positions and lengths. For instance, knowing that a name (CUSCDE) is made up of two mnemonics, each three characters long, you stand a fair chance of guessing what it represents:

CUS + CDE = Customer code

If, on the other hand, it could also be made of any other combination of abbreviations, guessing is more difficult:

The most efficient (giving maximum recognizability for minimal size) form of mnemonic is three characters long, as in most CL mnemonics.

Consonants are generally more significant for distinguishing names than vowels. The information content of a consonant (which distinguishes between from around twenty other letters) is greater than that of a vowel (which distinguishes from about five other vowels).

For example:

Contrast: ..a. .oe. ..i. .a.?

with: wh . t d . . s th. s s . y?

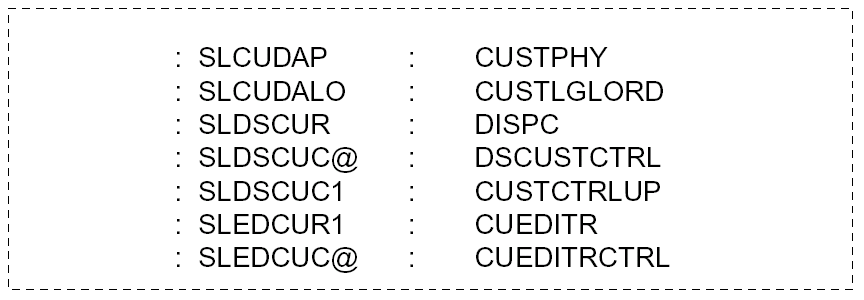

It is easier to carry out pattern matching on items that are strictly comparable. A column of names is easier to scan if the names are aligned as shown in the following example.

Program types: RPG CL PLI CBL BAS PAS (MI)

File types: PHY LGL DDM DSP MXD BSC CMN PRT DKT TAP CRD SAV

The structure of OS/400 sets basic restrictions on the uniqueness of names: to what extent should you apply further restrictions? Should program names be unique not just within an application, but across all applications held on the machine? Different versions of the same program, however, may have the same name but be in different libraries.

You usually want uniqueness at an object level for application objects, as it enables an object to be identified simply by its name. At a lower level it is only useful in database entities, files, formats, or fields, which may be common to many different applications.

It is also useful if message identifiers are unique, because once a message has been sent, there is generally no indication of the message file from which it was obtained.

The OS/400 object hierarchy also has a bearing on the significance of names for making distinctions, both as to the nature of the distinction, and as to the number of distinctions.

| Copyright © 2011 CA. All rights reserved. | Tell Technical Publications how we can improve this information |